This post originally appeared in the monthly farm animal welfare newsletter written by Lewis Bollard, program officer for farm animal welfare. Sign up here to receive an email each month with Lewis’ research and insights into farm animal advocacy. Note that the newsletter is not thoroughly vetted by other staff and does not necessarily represent consensus views of Open Philanthropy as a whole.

People love animals. Cute cat videos rule TikTok and YouTube, the Puppy Bowl clocks up 420M social media views, and Disney movies venerate animated creatures. Two thirds of Americans have at least one pet and 88% of them consider their pets to be family members, whom they lavish $137B on annually — more than the economic output of most nations.

People also hate animal abuse. Hollywood movies proudly proclaim “no animals were harmed,” while social media platforms all claim to ban content involving cruelty to animals. Ask ChatGPT if animal abuse is wrong and it drops its standard moral neutrality in favor of an empathetic “yes.”

A 2019 Faunalytics survey found that most Americans agreed that “people have an obligation to avoid harming all animals,” while a 2015 Gallup survey found that fully a third of Americans believe animals deserve “the exact same rights as people to be free from harm and exploitation.”

Even the worst politicians and corporations don’t dare defend animal cruelty publicly. Vladimir Putin is a self-proclaimed animal lover who made time between invasions of Ukraine to sign an animal cruelty bill into law. Tyson Foods claims to view the handling of animals as “an important moral and ethical obligation” — even as its contractors confine billions of them in abysmal conditions.

Our laws reflect this. Animal cruelty is a crime in most nations and a felony in every US state. In many cases, abusing an animal is punishable by a term of one to 10 years in prison — a similar punishment to assaulting a human. As legal scholar Cass Sunstein points out, these laws implicitly acknowledge that animals have “rights” — legally enforceable protection from harm — even if those rights are seldom enforced.

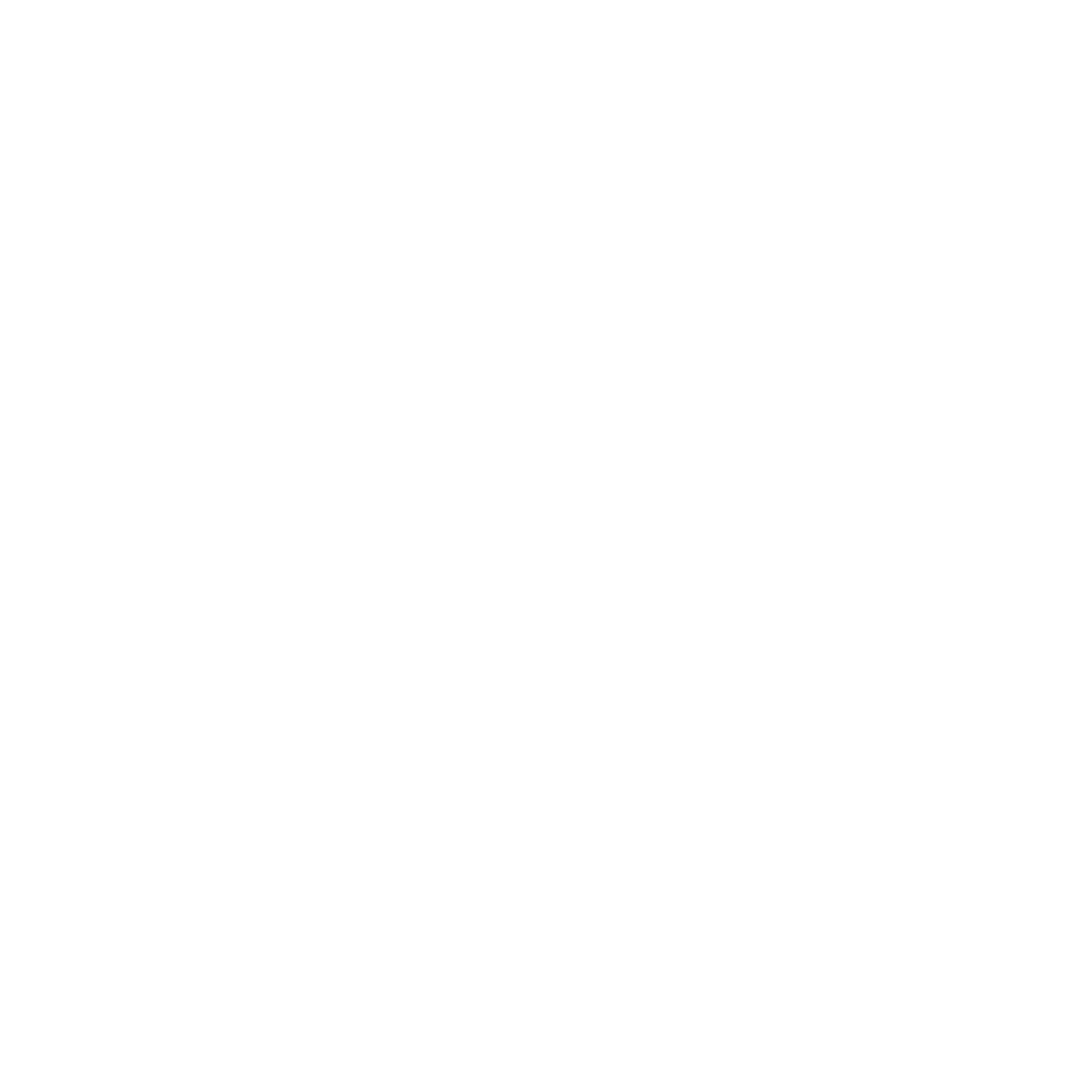

These laws typically exempt farm animals. But popular concern doesn’t: in a 2018 Faunalytics survey, 62-79% of Americans, Brazilians, Indians, and Russians agreed “that animals used for food have approximately the same ability to feel pain and discomfort as humans.” (Fewer Chinese agreed, but in a 2021 survey, more than 80% said it was somewhat or very important that mammals and birds are well cared for.) In a recent survey by Michelle Sinclair and colleagues, over 75% of respondents in 14 diverse nations agreed that the welfare of farm animals “is important to me” — a similar share to those who said so for companion animals.

And yet we also have factory farms, which confine over a dozen animals for every human alive on earth, in conditions so wretched that they have to be exempted from animal cruelty laws. What’s going on? How to explain the gulf between our belief, that we love animals, and the reality, that we torture them on an unprecedented scale?

Some animals are more equal than others

Popular theories blame our cognitive dissonance about animals on science, the law, popular culture, anthropocentric bias, and linguistics. Science reduces animals’ cognitive complexity into arbitrary tests like whether they can recognize themselves in a mirror. (Dogs can’t, but they can recognize their own scent, which we can’t.) The law reduces living, feeling, sentient beings to mere property. Popular culture celebrates dogs and cats, but seldom chickens or fish. Anthropocentric bias leads us to favor animals that look like human infants, with rounded faces and big eyes. Even our language, full of euphemisms like “meat processing” and “depopulation,” obscures the reality of what we’re doing to animals.

There’s something to all this. But I’m not sure it explains why we mistreat animals.

Consider mice and rabbits. Science recognizes their complexity, which is why both are model organisms for human neuroscience, including for complex cognitive ailments like depression and anxiety. Animal cruelty laws, which typically cover at least mammals, nominally protect them — even if the laws are seldom enforced. Popular culture celebrates them: there are few more famous animals than Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny. Anthropocentric bias should favor them: baby mice and rabbits are adorable (see below). And our language hardly hides our use of them: “mouse traps” and “rabbit meat” are euphemism-free. Yet we poison, trap, experiment on, and factory farm them by the hundreds of millions.

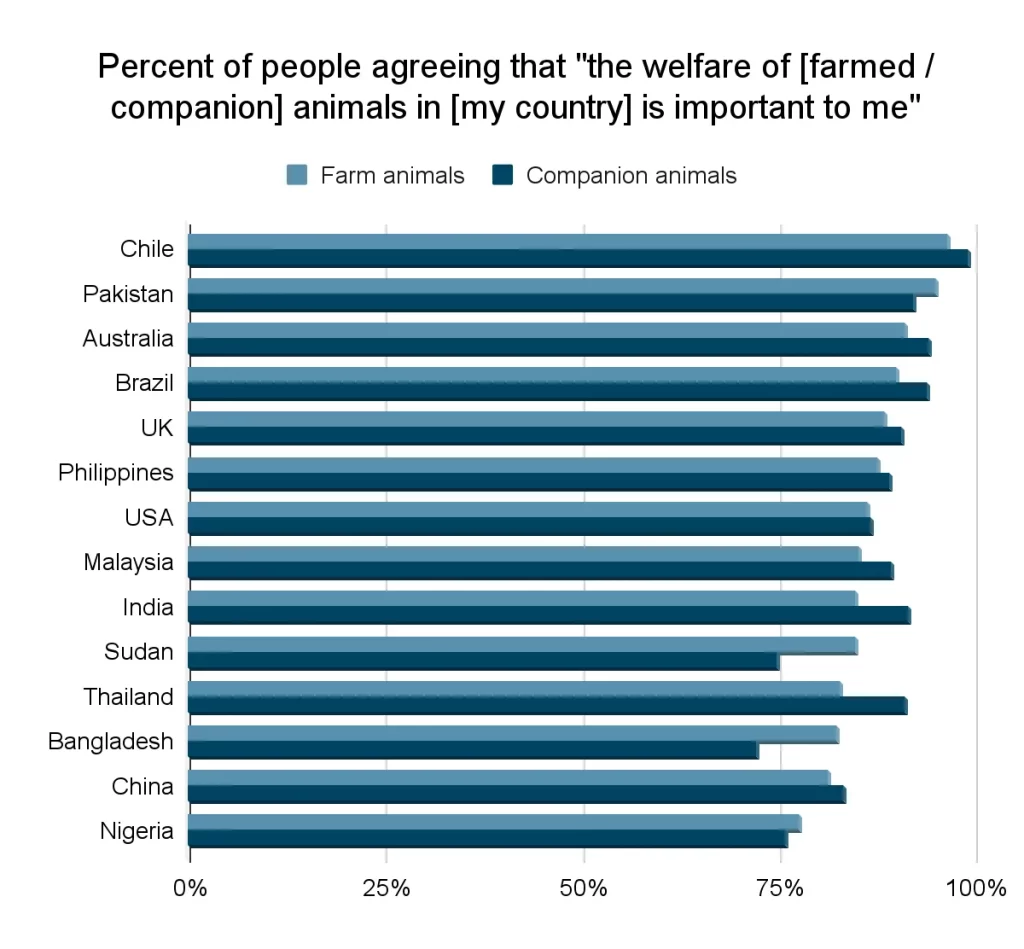

Another popular theory blames the limits of our moral circle. We love animals inside it — pets and charismatic wildlife — and disdain those outside it — pests and food. Sure enough, a recent study by Bastian Jaeger and Matti Wilks found that Americans, Australians, and Brits rated dogs and elephants as deserving much more moral concern than fish and rats (see below). But they also rated cows as highly as members of the opposing political party — not bad for a bovine.

And moral hierarchies are confusing. The Sinclair study found a much flatter hierarchy when they asked people in 14 countries about the relative importance of the welfare of different species. Chickens scored as highly as dogs, while fish swam ahead of turtles. Nor are moral circles static: depending on the time and place, rabbits are pets, wildlife, pests, and food.

Apathetic human, hidden animal

A simpler explanation is that people abuse animals when it’s convenient to do so, normally because there’s money to be made. Or in the words of the great Ruth Harrison, a forgotten founder of the modern farm animal movement: “if one person is unkind to an animal it is considered to be cruelty, but where a lot of people are unkind to animals, especially in the name of commerce, the cruelty is condoned and, once large sums of money are at stake, will be defended to the last by otherwise intelligent people.”

Yet only a tiny fraction of people systematically abuse animals. Factory farms and slaughterhouses employ far less than one percent of the world’s population — and the bosses calling the shots are fewer still. So why do the rest of us allow, and pay, them to abuse animals?

I blame ignorance and apathy. Most people have no idea how farm animals are treated. Factory farms don’t welcome visitors; the one that did, Fair Oaks Farms (“Dairy Disneyland”), turned out to be hiding a few things. Sentience Institute surveys find that most Americans agree that “the animal foods I purchase … usually come from animals that are treated humanely.”

That’s partly thanks to misleading labeling — leading brands of factory farmed chicken are labeled “all natural” and “humanely raised.” It likely also owes to our disbelief that salt-of-the-earth farmers, revered in children’s books and trusted by 88% of Americans, would abuse animals.

But I suspect we mostly just don’t want to know. Unlike other social crises, like climate change or rogue AI, farm animal abuse will never affect us or our children personally. Humans have a millenia-long history of ignoring or belittling moral crises that don’t affect them personally; why stop now?

It may not help that the most commonly proposed solutions — eating less meat or going vegan — ask a lot of us. Garrett Broad, who has run focus groups and surveys on our attitudes toward animals, concludes, “People adamantly did not want to stop caring for their pets, and they weren’t ready to give up meat either.”

If they only knew…

What to make of all this? It’s weird, even infuriating, that most humans consider themselves animal lovers while allowing the greatest abuse of animals in human history to continue unchecked. But it also gives me some hope.

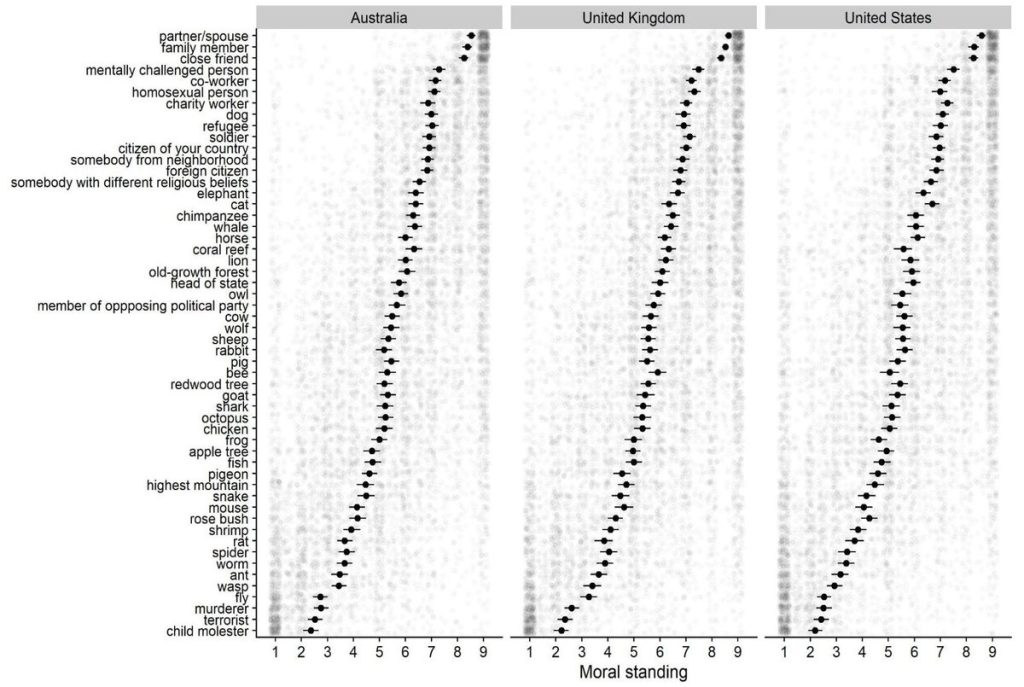

Most social movements have to persuade people to agree with them. We don’t: most people already oppose abusing farm animals. In a 2022 survey, Bryant Research found that just 2-13% of Brits thought common factory farming practices were “acceptable.” In Faunalytics’ survey, a majority of Americans, Brazilians, Chinese, Indians, and Russians backed a law to require farm animals to be treated more humanely.

Our task is to mobilize that support into corporate and legislative change. That’s not easy: ignorance and apathy are powerful opponents — as is the farm lobby. But the industry’s apparent power rests on a tenuous foundation. Its practices are so unpopular that its only hope is to hide them behind ag-gag laws and locked doors. That’s seldom worked for industries in the past; just ask Big Tobacco.

It also creates an opportunity for advocates. Undercover investigations and corporate campaigns work because the disconnect between factory farm conditions and consumer perceptions is so great. The mere act of exposing those conditions is enough to shock consumers.

Advocates sometimes shy away from talking about farm animals, preferring to talk about more human concerns like our health. I think that may be a mistake. People’s love of animals, and distaste for cruelty, is our greatest asset. We should use it.