Published: February 2015

Center for Popular Democracy (CPD) staff reviewed this page prior to publication.

Note: This page was created using content published by Good Ventures and GiveWell, the organizations that created the Open Philanthropy Project, before this website was launched. Uses of “we” and “our” on this page may therefore refer to Good Ventures or GiveWell, but they still represent the work of the Open Philanthropy Project.

The Center for Popular Democracy is running a campaign (“Fed Up”) that aims to prevent premature tightening of monetary policy and encourage greater transparency and public engagement in the governance of the Federal Reserve. We previously contributed $100,000 to help the campaign get started.

While we remain uncertain about the campaign’s prospects for making an impact, it has demonstrated some preliminary success during the last few months. Our best guess is that the campaign is unlikely to have an impact on the Fed’s monetary policy, but that if it does, the benefits would be very large. Additionally, we see some value in the campaign’s call for greater transparency and public engagement in the selection of regional Federal Reserve Bank leadership, and in enabling CPD to experiment with an advocacy campaign in macroeconomic policy.

Based on these considerations, we decided to grant an additional $750,000 to the Center for Popular Democracy to support the Fed Up campaign. We anticipate that this grant will make up roughly 75% of the campaign’s overall funding for the year.

GiveWell staff member Alexander Berger has led our work on macroeconomic policy to date and was responsible for initial drafting of this page. Unlike much of our other output, the complexity of the debates in this area has made it impractical for other GiveWell staff to construct and check a complete trail of evidence and counter arguments for each claim in this review. (More on our process for forming and vetting the views contributing to this grant below.) As a result, while we stand behind the content of this page, the case for many of our beliefs has not been fully captured in what we’ve written up.

1. Background

1.1 Campaign overview

Fed Up is a campaign run by the Center for Popular Democracy in association with 19 other progressive national advocacy organizations, unions, think thanks, and regional community-based organizations.1 The campaign targets the Federal Reserve, and its stated goals are both substantive (to “create a strong and fair economy”) and procedural (to “create a more transparent and democratic Federal Reserve”).2

The campaign’s current projected budget for 2015 is around a million dollars, with spending breaking down roughly evenly between two components:3

- Subgrants to 13 regional partner organizations.

- National staff time (~75%), research support (~15%), and other campaign costs (~10%).

This budget was informed by our decision to commit $750,000; an earlier draft was about 50% more ambitious in terms of spending.4 In addition to our commitment, the campaign has also raised $100,000 for its 2015 operations from another foundation, and anticipates some continued fundraising into 2015.5

The campaign envisions a number of different potential activities, with substantial variation based on decisions made by regional partner organizations. These activities largely break down into two categories: efforts to make clearer to Fed decision-makers the humanitarian stakes of their decisions, and efforts to credibly demonstrate that decisions by Fed policymakers will be subject to substantial public scrutiny.6 CPD asked us to keep the lists of specific campaign activities they’ve considered confidential on the grounds that publication might undermine their effectiveness. Future updates will look back on the specifics of CPD’s activities.

1.2 Organization overview

CPD was formed from a merger of two smaller organizations (one of which was also called CPD) at the beginning of 2014.7 Their current annual budget is roughly $8 million, and they have an affiliated 501(c)4 organization (Action for the Common Good) with an annual budget of about $2 million; together they have about 50 staff members.8

CPD is a progressive national advocacy group that works with local community groups across the country to promote their agenda.9 About half of their funding comes from the Ford, Open Society, and Wyss Foundations, and relatively little of it is unrestricted.10

We have not investigated CPD’s track record in depth. Program officers for other foundations that we asked about CPD in informal conversations reported generally positive impressions. One example of a campaign that CPD reports was successful was the “Campaign for a Fair Settlement,” undertaken prior to the merger, which pressured the Department of Justice to pursue a sizable settlement against banks that played a role in the financial crisis.11

Overall, our view about this grant is driven far more by our view of the campaign than by our assessment of CPD as an organization.

1.3 Campaign progress to date

To date, the campaign has conducted two major public activities, largely aimed at driving press attention:

- Protests at the Federal Reserve’s August meeting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

- A meeting with Federal Reserve Board Chair Janet Yellen in Washington, D.C. in November.

Before the August protests at Jackson Hole, CPD and 70 other progressive advocacy groups issued an open letter calling on the Fed to keep interest rates low until wages rise further, which prompted some initial media coverage.12 The protesters at Jackson Hole were covered widely in the media, including stories in the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Associated Press, Reuters, and Bloomberg News, amongst others, and the group met with Kansas City Fed President Esther George for about two hours.13 Binyamin Applebaum, a New York Times economics reporter who was at the conference, said, “Their presence has been mentioned repeatedly by Fed officials and speakers, suggesting that it has made an impression.”14

Prior to their November meeting with Yellen, CPD and partner organizations issued open letters calling for greater transparency and community engagement in the selection process for the new presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks in Philadelphia and Dallas (whose current presidents had both announced plans to retire in 2015).15 The meeting, and CPD’s press conference prior to it, again received widespread coverage, leading to articles in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Bloomberg News, and Associated Press, amongst others.16 Soon after the initial New York Times report about the open letters, the Dallas Fed announced the specific retirement date for their president and the name of the search firm hired to seek his replacement, while the Philadelphia Fed also announced the name of their search firm and set up a public-facing email to receive input.17 In addition, at the national level the Fed has publicly disclosed more information about the selection process for regional bank presidents and announced the formation of a new “Community Advisory Council.”18 The group’s meeting with Yellen triggered a response from those who hold different views about the appropriate stance of monetary policy, with a Wall Street Journal editorial condemning the effort and a conservative group holding a press conference outside the Fed to counter the campaign’s message.19 Some reporters writing about the meeting interviewed former Federal Reserve officials, whose reactions we would classify as mixed.20

Overall, we see these early actions as supporting two premises of the campaign, and reducing the risks associated with failure on either of these assumptions:

- The campaign will be able to interact with Fed policymakers.

- The campaign will be able to draw significant media coverage.

However, we continue to see the question of whether the campaign might have any more substantive impact as an open one.

2. Policy goals

2.1 Substantive goals

The campaign describes three substantive goals:

- Good Jobs for All: The Federal Reserve should commit to building a full employment economy. It should keep interest rates low so that wages can rise significantly and everybody can find a good job.

- Investment in the Real Economy: The Fed should use its existing legal authority to provide low- and zero-interest loans so that cities and states can invest in public works projects like renewable energy generation, public transit, and affordable housing that will create good new jobs.

- Research for the Public Good: The Fed should study the harmful effects of inequality and examine how policies like raising the minimum wage and guaranteeing a fair workweek can strengthen the economy and expand the middle class.21

We wouldn’t necessarily endorse these priorities verbatim. We see the first one as the key substantive priority, and would summarize it as suggesting that Federal Reserve policy should be somewhat more dovish at the margin, i.e. erring on the side of keeping interest rates lower longer than it might currently plan to. We think that such a change would likely be very beneficial in humanitarian terms. However, monetary policy is extremely technical and subject to widespread disagreement, so we could fairly easily be wrong on the merits, a risk we elaborate on below.

2.1.1 Desirability of these goals on the merits

The central reason we believe that marginally more dovish Fed policy relative to the current baseline would carry net benefits is that, at roughly their current rates, we see unemployment as more costly in humanitarian terms than inflation. Our view comes partly from the impressions we’ve formed on following public debates on macroeconomic policy, and appears consistent with what we’ve found in a relatively cursory review of the literature:

- Though there is empirical evidence that high levels of inflation (e.g. above 8%) harm economic growth, we are not aware of empirical estimates of the costs of inflation at relatively low values (e.g. under 5%).22

- Model-based estimates of the welfare costs of inflation (typically fit to some kind of economic data) yield widely varying results, and we have not conducted a systematic review of the literature. Our impression is that estimates based on the demand for money suggest that overshooting on inflation by 1 point would lead to a welfare loss of between ~0.02% and ~0.07%.23 However, estimates based on dynamic models that incorporate non-inflation-indexed portions of the tax code can yield much higher results (e.g. welfare costs of 0.3-0.5% per point of inflation).24 Other prominent estimates based on relatively simple New Keynesian models suggest that central banks will maximize welfare by placing substantially higher weight (e.g. 10-20x more) on inflation stabilization than unemployment, due to the welfare costs of price dispersion caused by inflation, but don’t specify welfare costs of a point of inflation.25 (Our impression is that more recent work by the authors of these models tends to argue in favor of price-level or nominal GDP (NGDP) targeting, which, with the current price and NGDP level well below the pre-crisis trend, would argue in favor of continued expansionary monetary policy.26) Given the fairly wide range of findings and our lack of familiarity with the methods involved, we have not placed heavy weight on these findings.

- We believe unemployment is directly costly in humanitarian terms, reducing happiness and income for the unemployed and their neighbors, with potentially adverse long-term impacts on human capital and we have seen some literature supporting this idea.27

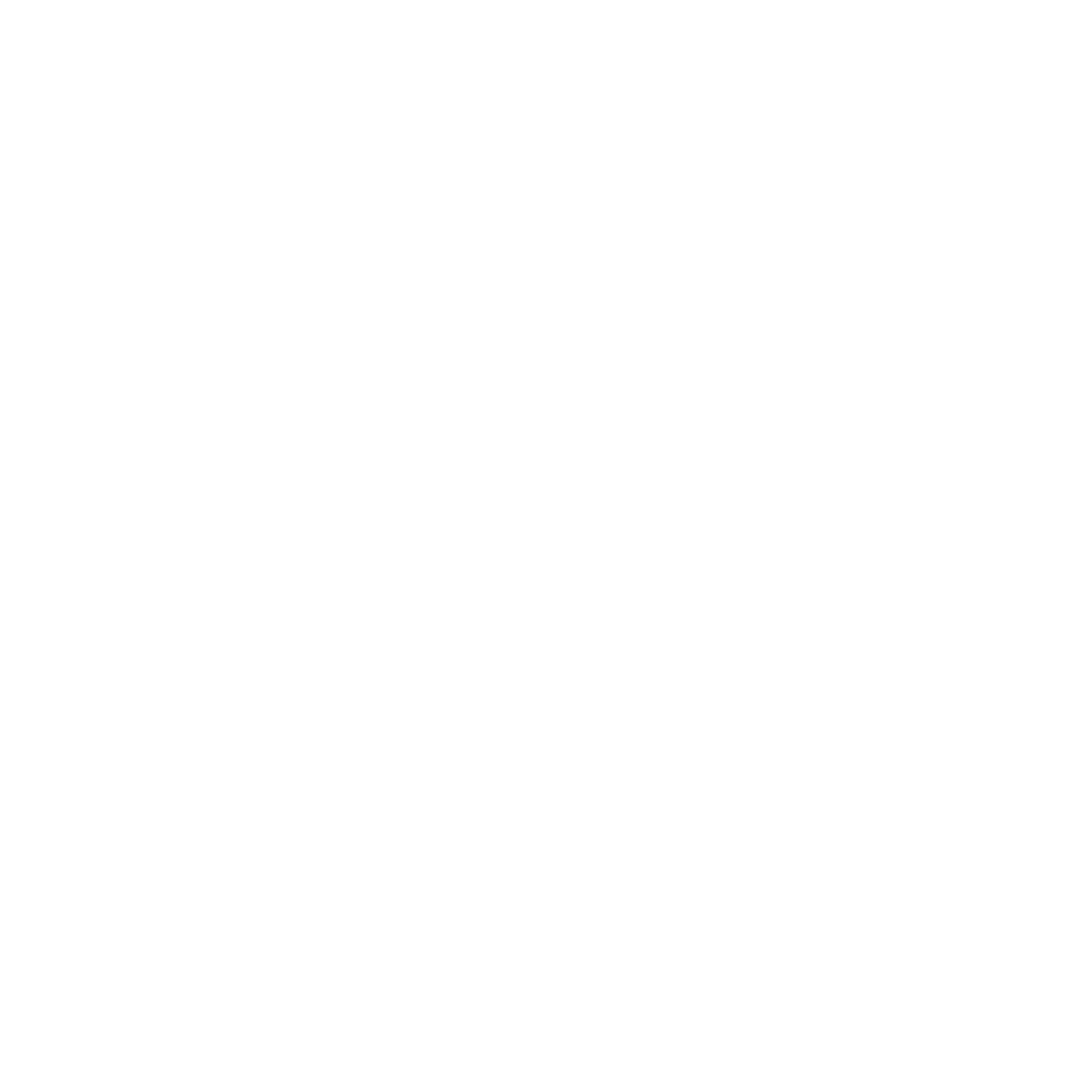

- Additionally, a slack labor market may reduce wage growth for lower-income people. This idea is intuitive to us, and we have seen some literature supporting it. Using data from 1989-2007, the Economic Policy Institute estimates that increasing unemployment by 1 point decreases annual nominal wages for the bottom decile of men by 1.96%, for the bottom decile of women by 1.49%, and for median wage men and women by ~0.9%.28 Katz and Krueger 1999 use data from 1973-1998 and a similar methodology to estimate that a one point increase in the unemployment rate reduces wages at the tenth percentile by 1.57% and at the median by 0.86%.29

- Empirical research using subjective well-being assessments also supports the conclusion that unemployment should be weighted more heavily than inflation. Di Tella, MacCulloch, and Oswald 2001 uses survey data on life satisfaction from 12 European countries over the period 1975-1991 to estimate that a point of unemployment is 1.7 times as socially costly as a point of inflation.30 Using similar data and methods but a larger set of countries (16) and a longer time period (1973-1998), Wolfers 2003 estimates that a point of unemployment is roughly 4-5 times as socially costly as a point of inflation.31 Blanchflower et al. 2014 uses, again, a broader set of European countries (31) over a longer time period (1975-2013) and finds that a point of unemployment carries roughly 5 times as much social cost as a point of inflation.32 We’re not aware of significant literature arguing for the opposite conclusion based on subjective well-being data, though we have not conducted an exhaustive search.

While we believe that at current levels, a point of unemployment is more costly than a point of inflation, central banks cannot arbitrarily trade off unemployment and inflation: in the long run, efforts to permanently push unemployment too low would result in the unanchoring of inflation expectations and an inflationary spiral.33 However, inflation expectations are extremely well-anchored right now, with survey-based measures broadly stable at around the Fed’s 2% target and market measures of expectations generally below target.34 This suggests that the Fed should be able to keep rates low to further reduce unemployment while having only a small impact on inflation (and be pushing it in the desired direction—towards the 2% target).35 More generally, short run tradeoffs between unemployment and inflation are not believed to be 1:1. Conventional estimates tend to suggest that keeping unemployment a full point below the “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment” for a year would result in inflation 0.5 points higher for the indefinite future, with more recent research suggesting a somewhat lower tradeoff.36

In addition to this central argument from the welfare asymmetry of inflation and unemployment for keeping interest rates low when inflation is below target and expectations are well-anchored, we also see the risks from tightening too soon as outweighing the risks from tightening too late. The Fed’s recent experience struggling to provide sufficient monetary stimulus at the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates suggests that it is worth being disproportionately careful to avoid tightening too soon, in order to avoid a rapid return to the zero lower bound, and the attendant risk of not being able to stimulate adequately, in the future.37 Market participants currently estimate the probability of the Fed being back at the zero lower bound within two years of initially raising rates as roughly 20%.38 On the other hand, the Fed is capable of tightening more than currently planned in order to control inflation should it emerge later.

A relatively tight labor market seems unusually unlikely to prompt high inflation today because corporate profits are at a record high while the labor share of income is historically low, though if those factors are driven by secular trends, a tight labor market may cause inflation rather than shifting profits to wages.39

Finally, estimating the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is quite challenging and involves significant uncertainty.40 In the face of such uncertainty, testing the estimate to see whether unemployment below that level does in fact cause faster inflation could be prudent.41

2.1.2 Expert disagreement about these goals

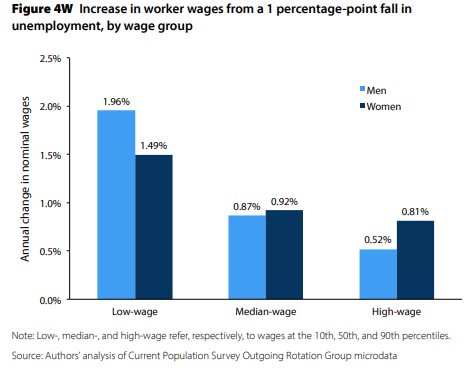

The Fed is extremely technocratic and well-informed, but officials within it nonetheless disagree about the appropriate path of monetary policy. For instance, members of the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC), which is responsible for setting monetary policy, disagree substantially about the appropriate pace with which to tighten in the coming years.42

In this section, we try to describe why some Fed officials with access to all of the information above, plus substantially more professional expertise, might nonetheless not agree with us that policy should err on the dovish side.

The below bullet points give our best guess at the main forces in play, with examples of people arguing that these are significant forces in the footnotes:

- Institutionally, the Federal Reserve sees the Volcker-era “victory over inflation” as its biggest success, and is reticent to run any risk of reversing it.43 More hawkish experts have regularly marshaled the example of 1970s-era inflation rates as a potential risk from keeping interest rates low (in spite of the fact that inflation expectations have remained well-anchored).44 (We think that more hawkish experts would react to this observation by defending the comparison to the 1970s and saying that recent Fed policy risks de-anchoring expectations.)

- Based on some prominent macroeconomic models, economists have often accepted the idea that central bankers should focus on inflation rather than unemployment in order to maximize welfare.45 Our impression is that these intellectual arguments have been assumed to argue against more expansionary monetary policy, because they did so in the past, even though they typically support more expansionary policy when inflation is below target and anchored and there is a remaining output gap (as is the case today).46 (We think that more hawkish experts would react to this observation by defending the models that recommend a strong focus on inflation and pointing out that the conventional Taylor Rule would recommend a non-zero interest rate at today’s unemployment and inflation rate levels.)

We are not very confident in these guesses, though, and overall, would not say that we have a strong sense of what drives expert disagreement in this area. Commentators have offered a variety of other explanations.47

The more hawkish presidents of the Philadelphia and Dallas Federal Reserve Banks have given speeches recently outlining their positions (see footnote),48, while the more dovish presidents of the Chicago and Minneapolis Federal Reserve banks have also offered their perspectives (see footnote).49 We encourage readers to consider both arguments.

2.1.3 Political context

Separate from the arguments above on the merits, we see two other reasons to support a campaign around these policy goals:

- In recent years, attention to and pressure on the Fed has come disproportionately from conservatives concerned about potential inflation risks, and less from liberals and those more concerned about unemployment.50 By amplifying more dovish voices, the campaign aims to bring the balance of popular attention to and pressure on the Fed into greater alignment with the distribution of expert opinion, and we see that as valuable. Were such voices already equally-represented in the popular discussion and advocacy around the Federal Reserve, we would be less likely to support this campaign.

- Even if we are wrong on the merits, we believe that broader discussion and debate around these issues is genuinely useful, and likely to produce marginally better monetary policy. Also, we expect that a campaign aiming to influence policy is more likely to push policy in the desired direction if it is directionally correct, so even in the context of a priori uncertainty about which direction is desirable, increasing advocacy on one side of it is more likely to be beneficial than harmful.

2.2 Procedural goals

The campaign describes three procedural goals:

- Ensure That Working Families’ Voices Are Heard: Fed officials should regularly meet with working families and community leaders, not just business executives, in order to get a more accurate picture of how the economy is working.

- Fed Officials Should Actually Represent the Public: In regional banks around the country, Fed leaders come overwhelmingly from financial institutions and major corporations. The Fed should appoint genuine representatives of the public interest to these governance positions.

- Create a Legitimate Process for Selecting Fed Presidents: In late 2015 and early 2016, the regional Fed banks will select their next presidents, who will serve five year terms. Currently, the process for selecting those presidents is completely opaque and involves no public input. That needs to change, so that the public has a real role in the selection process.51

We see these procedural goals as more unambiguously positive than the campaign’s substantive policy goals, though we struggle to evaluate how beneficial they would be.

Regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents, who attend FOMC meetings and vote on a rotating basis, are selected by their boards of directors.52 Each board has 9 members:53

- 3 Class A directors, elected by member banks to represent their interests

- 3 Class B directors, elected by member banks to represent the public

- 3 Class C directors, appointed by the Board of Governors in Washington to represent the public.

Only Class B and Class C directors are allowed to vote on the selection of regional bank presidents, and their appointment is subject to approval by the Board of Governors.54 The substantial role of Class B directors, who are elected by member banks, in selecting regional bank presidents strikes us as hard to justify.

While we don’t see a huge amount of direct utilitarian consequences for this consideration, there seems to be a strong procedural presumption in favor of a more credible, transparent selection process for regional Federal Reserve Bank board members and presidents.

3. Outside influences on the Federal Reserve

The Fed is an independent institution with wide authority over monetary policy. It is under no particular obligation to listen to a campaign by members of the public, and given its technocratic bent, may be particularly disinclined to do so.

To assess the likelihood that this campaign might be able to able to have an influence, we reviewed the literature on FOMC decision-making and considered the campaign’s specific plans.

The literature in this area consists of both reporting by journalists and (former) Fed officials, historical accounts based on vote data and meeting minutes, and econometric analyses, typically of the historical vote data. We attempted to read broadly in that literature, but we have not been exhaustive, and we have not reviewed the econometric evidence with the same depth and skepticism that we typically do in the context of top charities.

3.1 Research and reporting on FOMC decision-making

3.1.1 The role of the Chair

Most academic research suggests that Chairs carry disproportionate weight in the deliberation and votes of the FOMC. Quantitative and qualitative assessments of the Arthur Burns-era FOMC suggest that he accounted for around 40-50% of the FOMC’s decisions, while Alan Greenspan seems to have effectively dominated his FOMC, accounting for nearly 100% of its decisions.55 Less information is publicly available on the Bernanke and Yellen tenures, but they seem to both have more consensus-oriented styles that would put them closer to the Burns end of the spectrum (or perhaps even further along towards carrying less weight).56 Overall, we would guess that Yellen’s views do not dominate the FOMC like Greenspan’s did, but we would nonetheless estimate that they carry substantially disproportionate weight.

3.1.2 FOMC decision-making dynamics

According to the transcripts of FOMC meetings and anecdotal reports, FOMC members do not typically register a formal dissent even when they would prefer a different policy than the chair or the majority.57

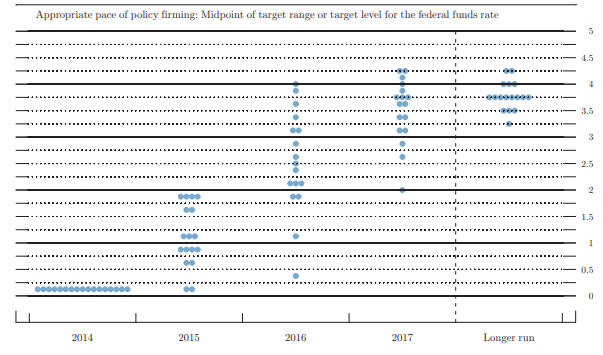

However, records of officially registered dissents are publicly available soon after meetings and give a sense of the dynamics of disagreement between FOMC members. Basic descriptive statistics on dissents are easy to capture:

- In the last 20 years, Governors have only dissented from FOMC decisions a total of four times, while regional bank presidents have dissented far more frequently.58

- Regional bank presidents tend to be more likely to dissent in favor of tighter policy, while Governors are more likely to dissent in favor of looser policy (though, as noted above, Governors very rarely dissent).59

- In the last 20 years, there have never been more than two dissents at a single FOMC meeting, except at the August and September 2011 and December 2014 meetings (which each had three).60

- Over the period 1978-2000, FOMC members, including both Governors and regional bank presidents, were more likely to dissent in favor of loose policy if the region they were from had above-average unemployment, and more likely to dissent in favor of tight policy if their regional had below-average unemployment (though the effect size is fairly small).61

Although legally speaking, a majority of the FOMC is sufficient to make decisions about monetary policy, in practice the committee does not appear to operate by majority rule (as the greater weight vested in the Chair attests). Evidence from transcripts of meetings during the chairmanship of Arthur Burns suggests that when members other than the chair make a difference, the distribution of influence seems to be somewhere in between a median voter (i.e. majority rules) and mean voter (i.e. average of what each member would like) model.62 Transcripts from the Greenspan era show that the FOMC followed his wishes, which suggests that it was driven more by the median voter than the average voter.63 An econometric model of rate-setting under the Burns and Greenspan FOMC finds that a consensus decision procedure best explains the observed patterns in the time series of interest rates (but doesn’t make use of minutes or dissent data).64 This makes it somewhat difficult to make firm predictions for the impact of changing the views or votes of individual members on overall committee decisions.

From the reports we’ve seen, regional bank presidents who do not have a vote at a given meeting appear not to have historically influenced the monetary policy outcomes of those meetings.65

With 10 voting members of the FOMC, as there are today, we would guess that the bulk of policy-making authority would fall on Chair Yellen, with the secondary authority falling to the second through fourth potential dissenters (presumably regional bank presidents).66

Interestingly, under the Greenspan chairmanship, Yellen, who was then a Governor and is now Chair, argued in favor of tightening in order to limit the risk of inflation, but did not dissent from Greenspan’s recommendation not to raise rates.67 Reflecting on that decision, Chappell et al. 2004 write:

While the arguments of Meyer and Yellen demonstrate a concern for inflation, they also illustrate another phenomenon. Despite an acknowledged risk of inflation, these members were willing to risk higher inflation to sustain the prevailing expansion. Even Greenspan recognized that this was implicit in his recommendation: ‘Having said all that, I fully acknowledge that we have a very tight labor market situation at this stage. I think identifying the current situation as an inflationary zone, as some have argued, is a proper judgment at this point. But it is a zone, not a breakthrough, and I would therefore conclude and hope, as I did last time, that we can stay at

‘B,’ no change’ (Transcripts, September 24, 1996, 31). In hindsight, Greenspan’s recommendation seems to have been the correct one. When Burns era policymakers had chosen to take similar risks, however, the outcomes had been less favorable.

3.1.3 Outside influences on the FOMC

The Fed guards its independence scrupulously, and political considerations are virtually never raised at FOMC meetings.68 However, the Fed is subject to outside attention and pressure.69

There is a substantial empirical and theoretical literature on “political business cycles,” in which the central bank might keep interest rates artificially low in the period prior to an election to increase the probability of re-election for the incumbent party.70 There is relatively limited econometric evidence in support of the idea, and it suggests that to the extent this has been an issue in the United States, it ceased to be one by the 1980s.71 More anecdotal accounts suggest that the Fed may have behaved politically in this way during the Arthur Burns chairmanship, but generally not since then.72

The most notable example we are aware of in which the Fed explicitly acted in response to political concerns in the post-Burns era was the shift to targeting monetary aggregates rather than interest rates during the Volcker era.73 In order to reduce inflation, the Fed needed to raise interest rates to unusually high levels. To get some of the more dovish members of the FOMC on board with raising rates and to deflect public criticism from the Fed, Volcker decided to start officially targeting monetary aggregates instead of the interest rates themselves.74 This was a strategy that Minneapolis Fed president MacLaury called for explicitly as political cover in prior FOMC meetings.75 There is some nuance to this example: it is not clear to us whether the move was driven more by the need to get the more dovish FOMC members to go along with raising rates or the need to deflect public criticism, though to the extent that the doves were worried about public criticism, which seems to have been the case, the two would overlap.

During the same period, a variety of interest groups protested against the Fed’s high interest rates (e.g. by mailing keys to represent unbuilt homes), with no apparent impact on Fed policy.76

Today, the financial industry probably dedicates the most organized attention to the actions of the FOMC, but there is little evidence of explicit lobbying on monetary policy issues, and the Federal Advisory Council (a group of bank representatives that advise the Fed) does not appear very influential.77 However, FOMC members, especially but not only regional bank presidents, likely interact much more with the financial industry formally and informally than they do with other sectors of society (e.g. the unemployed).78 According to her calendar, which was recently obtained by the Wall Street Journal under an open records request, Yellen has spent notably little time with bank executives since becoming chair in early 2014.79

3.2 This campaign

Based on the above summary of historical evidence, we think any outside efforts to influence U.S. monetary policy, including this one, are relatively unlikely to succeed. However, we think it has a non-trivial chance and that in this case the small chance of an important impact is sufficient to justify the investment.

In our view, the Dallas and Philadelphia Fed presidents retiring in early 2015, combined with the fact that all of the regional Fed presidents are up for renewal or replacement in January 2016, may give the campaign an unusual potential for influence.80 We see the most likely outcome of this campaign being an increase in the transparency with which regional Fed presidents are selected, with little or no impact on personnel decisions, but we can also envision scenarios in which the campaign results in somewhat different regional Fed personnel outcomes in 2016.

In terms of short-term monetary policy decisions, any impact seems relatively unlikely, but we could imagine the campaign making FOMC members marginally less likely to prefer hawkishness policies (or to threaten to dissent in favor of them) or marginally more likely to take a dovish stance relative to the center of the committee.

4. Rationale for the grant

4.1 The cause

We are considering macroeconomic policy as a potential focus area, and accordingly have prioritized it for possible “learning grants”. As part of our search for potential grant opportunities, we made an initial grant to CPD to help this campaign get started.

As we wrote in our initial writeup, many people we have spoken with have pointed to the lack of advocacy around the FOMC from those concerned about unemployment, and we have taken that argument as evidence that macroeconomic policy (in particular, advocacy regarding macroeconomic policy) may be neglected as a philanthropic cause relative to its importance.

4.2 Case for this grant

We see the case for this grant as being based on three potential impacts:

- A slim probability of moving monetary policy in a marginally more dovish (i.e. lower unemployment, higher inflation) direction. Based on the arguments above, we think this would be importantly positive from a humanitarian perspective.

- A reasonable chance of achieving some of the campaign’s procedural goals, including raising the level of transparency around how regional Fed presidents and board member are selected.

- Enabling CPD to experiment with an advocacy campaign in this area, potentially laying the groundwork for future advocacy efforts in the area, and testing our hypothesis that advocacy around macroeconomic policy is a promising and relatively neglected philanthropic area.

In deciding to make this grant, we’ve put the most weight on the first consideration.

Our best guess, based on the history of outside efforts to influence the federal reserve and the specifics of this campaign, is that the campaign will probably have no impact on monetary policy, but that it has a slim chance of making a very large impact, which justifies the investment.

The history of the Federal Reserve over the last few decades points to a few decisions as having been particularly influential (e.g. Volcker’s decision to target monetary aggregates, Greenspan’s decision to keep the unemployment rate below the then-estimated NAIRU during the late 1990s). The humanitarian impact of these decisions is difficult to calculate, but likely very large. Even a small chance (e.g. below 0.1%) of causing such an important change could have a high expected value.

We haven’t conducted a formal cost-effectiveness analysis for this grant, but we think it is likely to be competitive with other policy advocacy grants we’ve considered.

4.3 Room for more funding and fungibility

We think this campaign would be unlikely to occur at anything resembling the planned scale without our support. CPD has limited unrestricted funding,81 and is not aware of any other sources of funding that would consider funding the majority of the campaign.82

The initial budget we saw projected expenses of around $1.5 million, and we decided to contribute roughly half that amount. We tried to settle on an amount that would still require CPD to seek funding from other sources but would be sufficient to enable some level of campaigning to take place even if they failed to do so. We take the fact that the budget was revised downward after our commitment to support the notion that CPD wouldn’t be able to find the amount of funding that we’ve contributed from other sources, and that accordingly our contribution is largely non-fungible.

4.4 Risks to the success of the grant

We think this grant could fail in two broad ways:

- It could fail to achieve any policy impact.

- It could unintentionally cause harm by subjecting the Fed to more populist pressure, by causing a more powerful counter-mobilization, or by succeeding in pushing policy in the desired direction but turning out to be wrong about what direction would be desirable.

As discussed above, we think the first and more prosaic failure mode is more likely than not to occur: the campaign is unlikely to have a policy impact because the Fed is a relatively insulated, technocratic body. However, we could nonetheless still be over optimistic in believing the campaign has a non-negligible chance of having an impact, especially since we do not have a fully detailed understanding of the mechanisms through which the campaign aims to do so.

We also see this grant as carrying a limited but non-negligible risk of causing harm:

- A left-leaning campaign around monetary policy issues could conceivably risk destabilizing a technocratic consensus in support of the Fed.83 However, we doubt the existence of such a consensus: the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times editorialize in opposite directions on Fed decisions,84 the Cato Institute recently launched a new center on monetary policy aiming to “challenge [the Fed’s] credibility,”85 and members of Congress regularly call for audits of the Fed’s decision-making.86 Most economists strongly support the premise of central bank independence and oppose Congressional efforts to impose tighter restrictions on that independence,87 but we see this campaign as falling substantially closer to newspaper editorializing than to Congressional action to limit the Fed’s authority.

- Separate from general concerns about destabilizing a hypothetical technocratic consensus around the Fed, stronger mobilization by those who would prefer looser monetary policy could prompt a more powerful counter-mobilization by those who would prefer tighter monetary policy. To some extent this has already occurred, as described above, with a Wall Street Journal editorial and press conference by a conservative group in response to the campaign’s meeting with Yellen in November.88 However, to our knowledge, those responses received much less press attention than the initial campaign actions, and we would generally expect that pattern to continue. We do regard this as a substantial risk to the project.

- Perhaps most importantly, we could be wrong about the appropriate stance of monetary policy, in a number of ways:

- Inflation could be more likely to take off, or have worse humanitarian impacts, than we’ve been able to detect.

- Keeping interest rates low could promote financial instability or accelerate the onset of the next recession, either through increased instability or by causing a later, more extreme tightening. Former Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Stein has been a prominent advocate for the view that monetary policy should take financial stability concerns into account and, likely, tighten faster than inflation and output would suggest,89 but our impression is that most of the other people who have considered the issue have concluded that current monetary policy is not particularly risky and that it is more appropriate to ensure financial stability using “macroprudential” tools.90 Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher has emphasized the risk of recession due to needing to tighten more extremely at a later date.91 We think neither of these risks are dispositive.

- Monetary policy could be structurally less powerful in influencing unemployment and other humanitarian outcomes than we’ve assumed it is.

There is fairly widespread disagreement about these issues amongst economists, so it is not difficult to believe we could be mistaken. However, we see broader discussion and debate around these issues as genuinely useful, and likely to produce better monetary policy, even if we are mistaken. We expect that the campaign is more likely to succeed if it is directionally correct, so even in the context of uncertainty about whether we have correctly weighed these risks, increasing advocacy on one side is more likely to be beneficial than harmful.

Additionally, while we’ve tended to regard the campaign’s goals around accountability and transparency in the process of selecting regional Fed presidents as an unmitigated good, they could be a problem if people with opposing views about monetary policy were more likely to effectively exploit the new openness (which might be the case),92 or for unanticipated reasons.

5. Plans for learning and follow-up

5.1 Key questions for follow-up

Questions we hope to eventually try to answer include:

- What activities does the campaign undertake?

- What sort of attention does the campaign receive from policymakers or the press? We expect to largely rely on CPD’s press tracking to answer this question. We may check the transcripts of 2015 FOMC meetings after they are released in 2021 to see whether any of the FOMC members discuss meetings with workers that inform their perspectives on policy.

- To what extent does the campaign appear to influence monetary policy or the process of selecting regional bank board members and presidents? We think it is unlikely that the campaign will have an influence on monetary policy, or that we would be able to find out if it did, but nonetheless the possibility that it will plays a central role in our decision to make this grant, and we intend to at least ask the question. We are more optimistic that the campaign might influence the (transparency of the) process of selecting regional bank board members and presidents, and we also anticipate being more likely to be able to attribute changes to the campaign (since few other actors are mobilized on the topic).

- What do we learn from CPD and their approach to running a campaign like this? This is a relatively novel kind of philanthropy for us, and we expect that we will learn something about how to assess campaign funding opportunities in the future.

5.2 Follow-up expectations

We expect to have a conversation with campaign staff every 2-3 months for the duration of the grant, with public notes if the conversation warrants it.

Towards the end of the duration of the grant, we plan to attempt a more holistic and detailed evaluation of the grant’s performance, aiming to answer the questions above. As mentioned above, we may check the transcripts of 2015 FOMC meetings after they are released in 2021 to see whether any of the FOMC members discuss meetings with workers that inform their perspectives on policy.

We may abandon either or both of these follow-up expectations if macroeconomic policy ceases to be a focus area, or perform more follow-up than planned if this work becomes a more central part of our priorities.

6. Our process

CPD approached us for support for the campaign after hearing about our interest in potentially funding advocacy in this space. We made a previous grant of $100,000 to CPD to help get the campaign started.

Prior to deciding about this grant, we had a number of further conversations with Ady Barkan of CPD about the campaign’s plans, followed the initial progress of the campaign in drawing press attention, and looked more deeply into research on monetary policy.

We shared a draft version of this page with CPD staff prior to the grant being finalized.

6.1 Process for forming and vetting views on monetary policy

We became interested in macroeconomic policy as a potential focus area because of the attention it has drawn in the press and blogosphere since the beginning of the Great Recession. Many of our initial impressions about the topic were formed by reading blogs by economists such as Paul Krugman, Brad DeLong, Tim Duy, Scott Sumner, and Tyler Cowen (though this is not to suggest that these individuals agree with each other or with us).

In trying to form more confident views and to understand the perspective of the people who disagree with us, we pursued a number of avenues:

- Reviewing more of the academic literature on specific questions of interest (such as the welfare costs of inflation), typically by searching in Google Scholar and following citation networks. Because of the complexity of many macroeconomic models and the large size of this literature, we didn’t find this especially informative or conclusive, but we review what we found above. We didn’t do this at the level of detail that we do in some of our other work.

- Reading blog posts, op-eds, and speeches by prominent economists with more hawkish views.93

- Off the record conversations with a prominent conservative monetary economist and two former senior Fed officials.

7. Sources

| DOCUMENT | SOURCE |

|---|---|

| Appointment of Reserve Bank Presidents and First Vice Presidents | Source (archive) |

| Associated Press 2014a | Source (archive) |

| Associated Press 2014b | Source (archive) |

| Atkinson, Luttrell, and Rosenblum 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Ball 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Bernstein 2014 | Source |

| Bernstein and Baker 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Blanchflower and Posen 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Blanchflower et al. 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Blinder 2007 | Source (archive) |

| Bloomberg News 2014a | Source (archive) |

| Bloomberg News 2014b | Source (archive) |

| Bloomberg News 2014c | Source (archive) |

| Bloomberg News 2014d | Source (archive) |

| Chappell et al. 2004 | Source (archive) |

| Chodorow-Reich 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Clarida 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Coyne 2005 | Source (archive) |

| CPD Fed Open Letter | Source (archive) |

| CPD Federal Reserve Campaign Budget | Unpublished |

| CPD Federal Reserve Campaign Paper | Source |

| CPD Memo on the Alleged Insulation of the Federal Reserve from Political Pressure | Source |

| CPD – Our Meeting With Janet Yellen | Unpublished |

| Crump et al. 2014 | Source (archive) |

| DeLong 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Di Tella and MacCulloch 2007 | Source (archive) |

| Di Tella, MacCulloch, and Oswald 2001 | Source (archive) |

| Directors of Federal Reserve Banks and Branches | Source (archive) |

| Drazen 2001 | Source (archive) |

| Duy 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Economic Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents, December 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Economist 2014a | Source (archive) |

| Economist 2014b | Source (archive) |

| Economist 2014c | Source (archive) |

| EPI State of Working America 2012 | Source (archive) |

| Evans 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Fed Up 2015 Budget | Unpublished |

| Fed Up 2015 Budget Draft for GiveWell | Unpublished |

| Fed Up Campaign Plan | Unpublished |

| Fed Up Coalition Priorities | Source |

| Fed Up One Pager | Source |

| Federal Reserve Bank Presidents | Source (archive) |

| Feldstein 1997 | Source (archive) |

| Fernald 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Financial Times 2014 | Source |

| Fisher 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Mishkin 2008 | Source (archive) |

| FOMC Projections, June 2014 | Source (archive) |

| FOMC Transcript March 2008 | Source (archive) |

| FRED chart of five year and five year forward inflation expectations | Source (archive) |

| Gerlach-Kristen and Meade 2011 | Source (archive) |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Brian Kettering on October 16, 2014 | Source |

| Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, July 25, 2014 – FOMC Preview: Eyes on the Dashboard | Unpublished |

| Goldman Sachs Research US Daily: Q&A on “Why Renege Now?” (Hatzius) 9-15-2014 | Unpublished |

| Greider 1987 | Source (archive) |

| Helliwell and Huang 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Hilsenrath 2014 | Source (archive) |

| How is a Federal Reserve Bank president selected? | Source (archive) |

| IGM Survey on Congress and Monetary Policy | Source (archive) |

| IMF 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Ireland 2009 | Source (archive) |

| Katz and Krueger 1999 | Source (archive) |

| Kiley 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Kocherlakota 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Krugman 2014 | Source |

| Lucas 2000 | Source |

| Meade 2005 | Source (archive) |

| Meade and Sheets 2005 | Source (archive) |

| Meltzer 2010 | Source (archive) |

| Meyer 2004 | Source (archive) |

| Washington Post 2014a | Source |

| Notes from a conversation with Joe Gagnon on February 4, 2014 | Source |

| Notes from a conversation with Josh Bivens on February 6, 2014 | Source |

| Notes from a conversation with Laurence Ball on April 17, 2014 | Source |

| Notes from a conversation with Mike Konczal on January 23, 2014 | Source |

| New York Times 2014a | Source |

| New York Times 2014b | Source |

| New York Times 2014c | Source |

| New York Times 2014d | Source |

| New York Times 2014e | Source |

| New York Times 2014f | Source |

| New York Times 2014g | Source |

| New York Times 2015 | Source |

| PBS 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Plosser 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Reuters Fed Dove-Hawk Scale | Source (archive) |

| Reuters 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Riboni and Ruge-Murcia 2010 | Source (archive) |

| Schonhardt-Bailey 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Stein 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Sumner 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Survey of Professional Forecasters Fourth Quarter 2014 | Source (archive) |

| The Hill 2014 | Source (archive) |

| The Structure of the Federal Reserve System Board of Directors | Source (archive) |

| Thornton and Wheelock 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Washington Post 2014b | Source |

| Washington Post 2014c | Source |

| WSJ 2014a | Source (archive) |

| WSJ 2014b | Source (archive) |

| WSJ 2014c | Source (archive) |

| WSJ 2014d | Source (archive) |

| WSJ 2014e | Source (archive) |

| WSJ 2015 | Source (archive) |

| Weisenthal 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Wolfers 2003 | Source (archive) |

| Woodford 2001 | Source (archive) |

| Woodford 2012 | Source (archive) |

| Woolley 1984 | Source (archive) |

| Wynne 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Yellen 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Yellen and Akerlof 2004 | Source (archive) |